Backlinks

1 Deriving Rotational KE and Inertia

Given \(m_i\), mass, \(\vec{r_i}'\), location of the center of mass, \(l_i\), \(\omega\), the angular velocity, figure a \(KE_{tot,rot}\).

Because of the fact that the value \(\omega\) is in units \(\frac{d\theta}{dt}\), the rate of radians change, and we know of a radius of the spin \(l_i\), we could figure the velocity at which it is moving by simply scaling the change in radians up to a circle of radius \(l_i\), that is:

\begin{equation} V_i' = l_i \omega \end{equation}(note that, to understand this, radians \(\frac{arc length}{radius}\))

And so, substituting into the statement of \(\sum^N_{i=1} \frac{1}{2}m_i\vec{v_i}'^2\)

\begin{align} KE_{rot} =& \sum^N_{i=1} \frac{1}{2}m_i\vec{v_i}'^2 \\ =& \sum^N_{i=1} \frac{1}{2}m_i(l_i \omega)^2 \\ =& \sum^N_{i=1} \frac{1}{2}m_i l_i^2 \omega^2 \\ =& \frac{1}{2}\omega^2 \sum^N_{i=1} (m_i l_i^2) \end{align}1.1 Rotational Inertia

The right sum — the mass times the distance away from maxis of rotation (\(\sum^N_{i=1} (m_i l_i^2)\)) — is defined as the rotational (moment) of inertia (spinny mass). That is,

\begin{equation} I = \sum^N_{i=1} (m_i l_i^2) \end{equation}Replacing that value in the prior statement, the statement of \(KE_{rot}\) is defined as:

\begin{equation} KE_{rot} = \frac{1}{2}\omega^2I \end{equation}1.2 Rotational Inertia for a Ring

For a ring (that's perfectly circular) rotating on an axis perpendicular to the plane of the ring, the \(l_i\) — distance from axis of rotation — is the same value: namely, the radius \(R\) as the radius of a circle is the same for all positions. Meaning,

\begin{equation} l_i = R \end{equation}regardless of which value \(i\).

Hence, the value of \(KE_{rot}\) would be evaluated as…

\begin{align} KE_{rot} =& \sum^N_{i=1}(m_il^2_i) \\ =& \sum^N_{i=1}(m_iR^2) \\ =& R^2 \sum^N_{i=1}m_i \\ \end{align}Substituting \(M\) as the sum of all masses in the ring (\(M=\sum^N_{i=1}m_i\)), the statement is therefore:

\begin{equation} KE_{rot} = MR^2 \end{equation}1.3 Rotational Inertia of a Solid Sphere

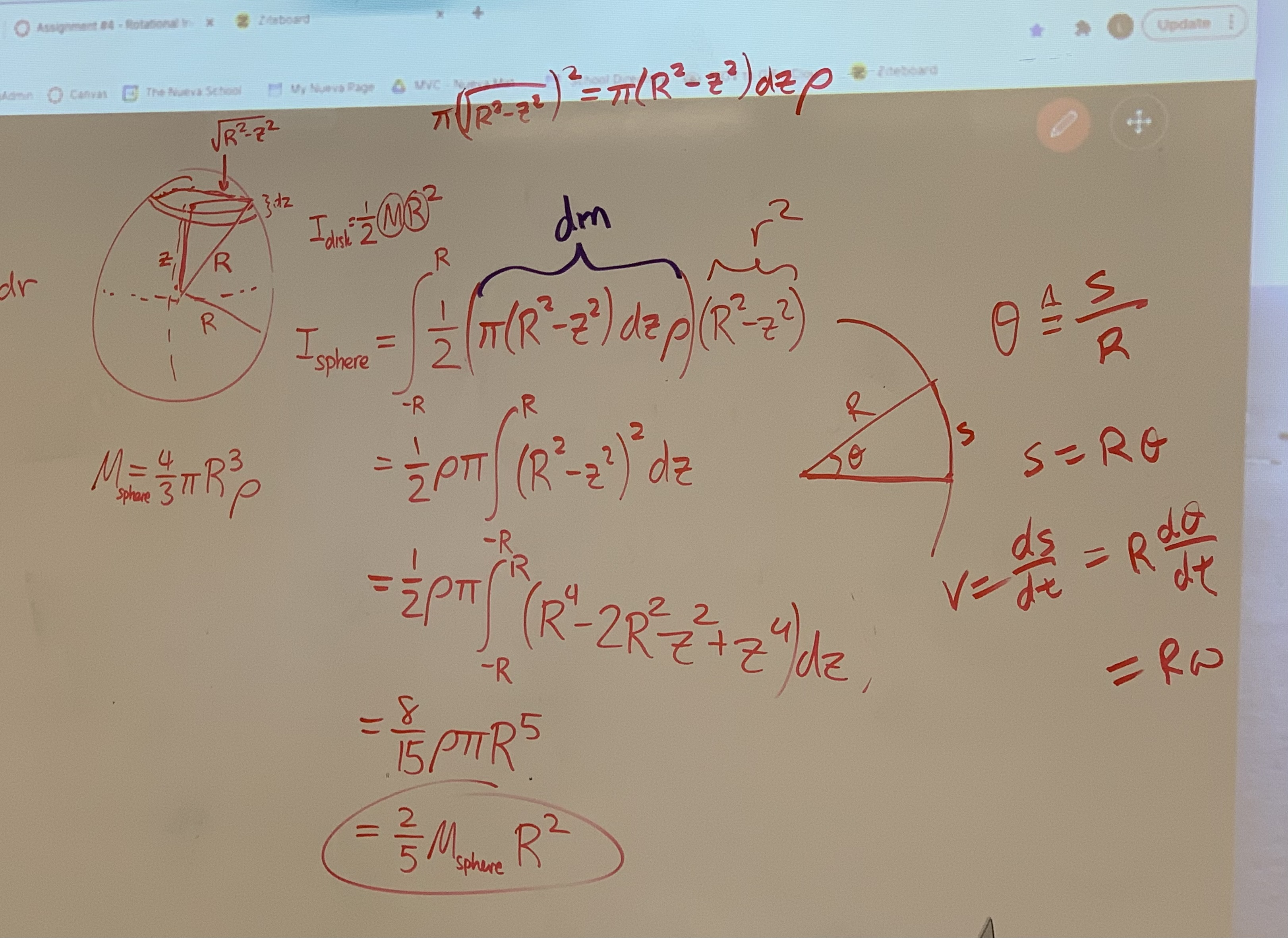

I believe that the rotational inertia of \(I_{sphere}\) to be less than \(I_{disk}\). This is because, as the dimension of the object increases, it would be easier to change its velocity (a disk is easier to spin than a ring, etc.). Hence, my intuition states that \(I_{sphere}\) would be lower than \(I_{disk}\).

Mathematically, as \(M\) is staying at the same value, in the disk case has more mass closer to the axis of rotation — meaning that the \(m_iR^2\) term would be smaller in more of the point masses than that of an object at a lower dimension. Hence, the sphere would have more points with lower \(m_iR^2\) terms than that of disk; hence, \(I_{sphere}\) would be less than \(I_{disk}\).

There is, also, an actual integral solution to this.

1.3.1 Actual Integral Solution

- Rings

Here is a ring, which we know:

\begin{equation} I= MR^2 \end{equation}A disk is bunch of small rings squisheified together, so the total \(I_{disk}\) is therefore:

\begin{equation} I_{disk} = \int^R_0 R^2 dm \end{equation}\(dm = 2\pi \sigma dr\): radius changes times the each of the radius times surface density (\(\sigma\)).

And so, substituting…

\begin{align} I_{disk} =& \int^R_0 r^2 dm \\ =& \int^R_0 r^3 2 \pi \sigma dr \\ =& 2r\pi\sigma \int^R_0 r^3 dr \\ =& \frac{1}{2}\pi\sigma r^4 \end{align}Replacing \(\pi \sigma r^2 = M\), because :why: exactly?

\begin{equation} I_{disk} = \frac{1}{2}Mr^2 \end{equation} - Spheres

I didn't follow quick enough to get this to be written down. But here's a pretty picture.

The gist is essentially to add up the tiny tiny disks that exist in a sphere to result in the moment of rotational inertia for a sphere.

2 Kinematics Equations

We begin by defining a coordinate system such that positive values are pointed "downwards". That is, as values increase in the positive direction, their corresponding vectors are pointed further towards the "down" direction.

Given \(a=a_0\), initial velocity \(v_0\), and position \(y_0\), we derive the kinematics equations.

\begin{align} a(t) =& a_0 \\ \int a(t) dt =& \int a_0 dt \\ v(t) =& a_0t + C \end{align}We are given that \(v(0)=v_0\). \(v(0) = C = v_0\), hence, \(C=v_0\). The velocity statement is therefore,

\begin{equation} v(t) = a_0t+v_0 \end{equation}Continuing with integration:

\begin{align} v(t) =& a_0t + v_0 \\ \int v(t) =& \int a_0t + v_0 dt \\ y(t) =& \frac{1}{2}a_0t^2+v_0t+C \\ \end{align}Again, substituting \(C = y_0\) by the same logic above — \(y(0) = C = y_0\), we derive the statement for the position equation.

\begin{equation} y(t) = \frac{1}{2}a_0t^2 + v_0t + y_0 \end{equation}But what if we want to do this in multiple dimensions? They will be vectors, for one.

\begin{align} \vec{a}(t) =& \vec{a_0} \\ \int\vec{a}(t)dt =& \int\vec{a_0} dt \end{align}and so on. The reason why we could do this is simply because \(\vec{a_0} = a_0_x \hat{i} + a_0_y\hat{j} + a_0_z\hat{k}\), and, perhaps unsurprisingly, integrals and derivatives and commutative and distributive across addition.

2.1 Proving \(v^2(t) = v_0^2 + 2a_0(y(t)-y_0)\)

We start at the statement for \(v(t)\), squaring it, and substituting the necessary statements.

\begin{align} v(t) =& a_0t+v_0 \\ \Rightarrow v^2(t) =& {a_0}^2 t^2 + 2a_0v_0t + v_0^2 \\ v^2(t) =& {v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (\frac{1}{2} a_0 t^2 + v_0t) \\ v^2(t) =& {v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (\frac{1}{2} a_0 t^2 + v_0t + y_0 - y_0) \\ v^2(t) =& {v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (y(t) - y_0) \end{align}It is therefore shown that:

\begin{equation} v^2(t) = {v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (y(t) - y_0) \end{equation}2.2 Proving \(\Delta y = \frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t\)

Showing \(\Delta y = \frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t\), defining \(\Delta y=y(t_2)-y(t_1)\) and \(\Delta t = t_2 - t_1\). Substituting the appropriate values for \(v(t)\), \(\Delta y\), \(\Delta t\) and solving…

\begin{align} \Delta y &= \frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2} (t_2 - t_1) \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{((a_0t_1+v_0)+(a_0t_2+v_0))}{2} (t_2 - t_1) \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{((a_0t_1t_2+v_0t_2)-(a_0{t_1}^2+v_0t_1)+(a_0{t_2}^2+v_0t_2)-(a_0t_1t_2+v_0t_1))}{2} \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{(a_0{t_2}^2+2v_0t_2)-(a_0{t_1}^2+2v_0t_1)}{2} \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{(a_0{t_2}^2+2v_0t_2+2y_0)-(a_0{t_1}^2+2v_0t_1+2y_0)}{2} \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= \frac{1}{2} a_0{t_2}^2+v_0t_2+y_0 - \frac{1}{2} a_0{t_1}^2+v_0t_1+y_0 \\ y(t_2)-y(t_1) &= y(t_2) - y(t_1) \\ \end{align}Hence, it is demonstrated that:

\begin{equation} \Delta y = \frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t \end{equation}3 Question regarding signage

The Kinematics Equations derivations above relied on the fact that the coordinate system was defined as "positive downwards". Were this not to be the case, constants would have to be redefined and the signs of most terms would be flipped:

Given \(a=-a_0\), initial velocity \(-v_0\), and position \(-y_0\), we (re)derive the kinematics equations.

\begin{align} a(t) =& -a_0 \\ \int a(t) dt =& \int -a_0 dt \\ v(t) =& -a_0t + C \end{align}We are given that \(v(0)=-v_0\). \(v(0) = C = -v_0\), hence, \(C=-v_0\). The velocity statement is therefore,

\begin{equation} v(t) = -a_0t-v_0 \end{equation}Continuing with integration:

\begin{align} v(t) =& -a_0t - v_0 \\ \int v(t) =& \int -a_0t - v_0 dt \\ y(t) =& \frac{-1}{2}a_0t^2 - v_0t+C \\ \end{align}Again, substituting \(C = -y_0\) by the same logic above — \(y(0) = C = -y_0\), we derive the statement for the position equation.

\begin{align} y(t) =& \frac{-1}{2}a_0t^2 - v_0t - y_0 \\ y(t) =& -(\frac{1}{2}a_0t^2 + v_0t + y_0) \end{align}As such, if the signage were flipped, terms of the kinematics equation would therefore be the negative of the original — that \(y'(t) = -y(t)\) if \(y'\) contains uses a flipped coordinate system. Leveraging the same property, therefore, we could derive quickly the other two statements with a flipped coordinate system:

\begin{align} \Delta y' =& \frac{-v(t_1)-v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t \\ =& -\frac{v(t_1)+v(t_2)}{2}\Delta t \end{align}and

\begin{align} v^2(t) =& {-v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (-y(t) - (-y_0)) \\ =& {v_0}^2 + 2a_0 (y_0 - y(t)) \end{align}4 Proving the Third Equation for \(V^2\)

We begin by deriving an equation of \(a(y)\) — acceleration as a function of position.

Based on first principles, the following is true:

\begin{equation} a(t) = \frac{dv}{dt} \end{equation}With apply the chain rule, we derive the following:

\begin{align} a(t) =& \frac{dv}{dt} \\ \Rightarrow \frac{dv}{dt} =& \frac{dv}{dy}\frac{dy}{dt} \\ \end{align}Integrating both sides w.r.t. position…

\begin{align} \frac{dv}{dt} =& \frac{dv}{dy}\frac{dy}{dt} \\ \Rightarrow \int \frac{dv}{dt}\ dy =& \int \frac{dv}{dy}\frac{dy}{dt}\ dy\\ \end{align}The right integral now requires some additional movement to solve.

\begin{align} \int \frac{dv}{dt}v\ dy =& v^2 - \int \frac{dv}{dy} v\ dy \\ \Rightarrow 2\int \frac{dv}{dy}v\ dy =& v^2 + C \\ \Rightarrow \int \frac{dv}{dy}v\ dy =& \frac{v^2}{2} + C \end{align}Substituting the right statement back into the original expression, and continuing to solve.

\begin{align} & \int \frac{dv}{dt}\ dy = \frac{v^2}{2} + C \\ & \Rightarrow \int \frac{dv}{dt}\ dy = \frac{v^2}{2} + C\\ & \Rightarrow 2ay + C = v^2 \end{align}Because of the fact that this expression is a value of \(v^2\), and that the constant is an offset of the value (as per calculated by \(2ay\)), we set \(C = {v_0}^2\). Additionally, \(y\) is an statement that represents the offset of \(y\) position, we set \(y = y(t)-y_0\) to represent the actual offset.

Hence:

\begin{equation} v^2 = 2a(y(t)-y_0) + {v_0}^2 \end{equation}