Backlinks

1 Fixing the Phineas Gage'd

The error exists on the \(z\) bounds: while most of the expression is correct, we will note that the cylinder crops out a small section for which there is no circle—and taking the \(z\) bounds between \([-1,1]\) would result in overcounting negative values (the "choppy bit" at the end of the cylinder). Hence, we need to figure out the heights at which the circle intersectns with the cylinder.

At the height of intersection, the radius of the sphere should be at \(\frac{1}{2}\). Solving for the height which this is at:

\begin{align} &\frac{1}{2} = \sqrt{1-z^2} \\ \Rightarrow & \frac{1}{4} = 1-z^2\\ \Rightarrow & z^2 = 1-\frac{1}{4}\\ \Rightarrow & z^2 = \frac{3}{4}\\ \Rightarrow & z = \frac{\pm\sqrt{3}}{2} \end{align}Taking the integral again, we will get—correctly—that the volume would be \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\pi\).

2 The volume of a sphere

We will build up a sphere via three directions. First, along the radius to figure \(r\), spanning across a circle by interlocking ever-larger rings, and building up a sphere by circular disks.

Taking the actual integral, then.

For the first integral \(\int_0^r dr\), it is trivial to get \(r\).

Taking the second integral:

\begin{align} &\int_0^{2\pi} r dr \\ \Rightarrow &\pi r^2 \end{align}Which is indeed the area of a circle as we expect. Finally, taking the third integral, we have to pay some care. Note that $r = \sqrt{R^2-h^2}$—by the Pythagorean theorem, where \(r\) is the lateral radius and \(R\) is the "hypotenuse" (i.e. actual radius) of the sphere. Therefore:

\begin{equation} r^2 = R^2-h^2 \end{equation}We wish to add along \(dr\) by \([-R,R]\), making:

\begin{align} &\int_{-R}^R \pi r^2\ dr\\ \Rightarrow &\pi \int_{-R}^R R^2-h^2\ dh\\ \Rightarrow &\pi \left\left(hR^2-\frac{h^3}{3}\right)\right|_{-R}^R\\ \Rightarrow &\pi \frac{4R^3}{3}\ \blacksquare \end{align}3 Single integral intersection

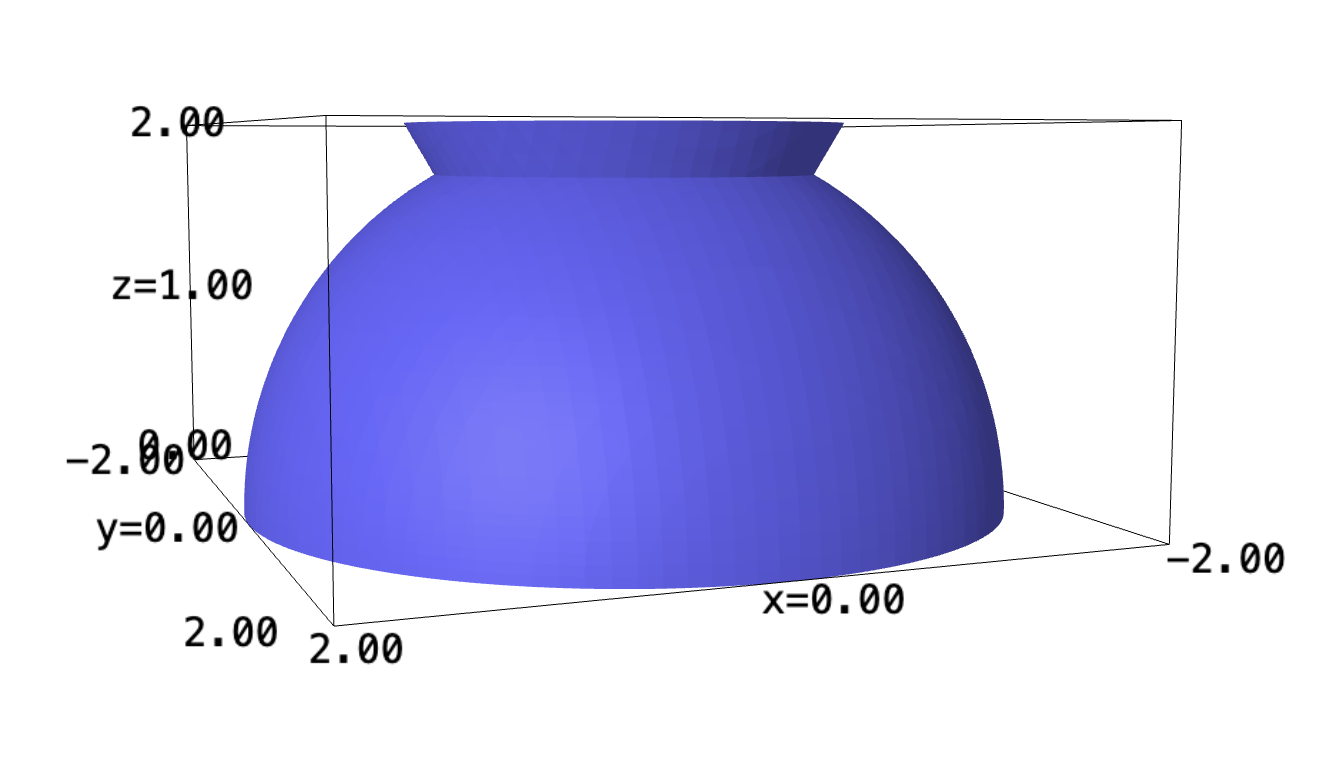

Let's first plot the shapes:

x,y,z = var("x y z")

implicit_plot3d(z^2==4-x^2-y^2, (x,-2,2), (y,-2,2), (z,0,2)) + implicit_plot3d(z^2==3*x^2+3*y^2, (x,-2,2), (y,-2,2), (z,0,2))

Let's figure the top end of the shape—where the two shapes intersect. That is, let's figure the shape where:

\begin{equation} 4-x^2-y^2 = 3x^2+3y^2 \end{equation}Solving for a equation for a circle:

\begin{equation} 1 = x^2+y^2 \end{equation}We can see that we need to figure a height \(z\) at which the radius is \(1\). Take the expression \(z^2=4-x^2-y^2\). We can see that, according to the above expression, \(-x^2-y^2 = -(x^2+y^2) = -1\).

Hence, \(z^2 = 3\), therefore \(z \approx \sqrt{3}\).

To take the integral, we will figure the radiuses squared by a function of \(z\):

\begin{align} &z^2 = 4-x^2-y^2\\ \Rightarrow & 4-z^2 = x^2+y^2 \end{align}We will further figure the radius squared for the other expression:

\begin{align} &z^2 = 3x^2+3y^2\\ \Rightarrow & \frac{1}{3}z^2 = x^2+y^2 \end{align}Finally, then, we take the integral:

\begin{align} &\int_0^{\sqrt{3}} \pi \left((4-z^2) - \left(\frac{1}{3}z^2\right)\right) dz\\ \Rightarrow &\int_0^{\sqrt{3}}\pi \left(4- \frac{4}{3}z^2\right) dz\\ \Rightarrow &\left\left(\pi 4z- \pi \frac{4}{9}z^3\right)\right|_0^{\sqrt{3}}\\ \Rightarrow & \frac{8\sqrt{3}\pi}{3} \end{align}4 Area under Bell Curve

Ok, it seems like this is a prime time to use implicit integration. We will define:

\begin{equation} I = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-x^2} dx \end{equation}We will declare \(I^2\), the square of the integration. We will rename the variable to \(y\) for one of the cases:

\begin{equation} I^2 = \left(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-x^2} dx\right) \left(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-y^2} dy\right) \end{equation}Hey, look! A double integral. Let's write it as such:

\begin{equation} I^2 = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-(x^2+y^2)} dx\ dy \end{equation}The \(x^2+y^2\) makes it seem like it would be nice in polar terms; so, let's do that:

\begin{align} I^2 &= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int^{2\pi}_{0} e^{-r^2}\ r d\theta\ dr\\ &= 2\pi \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-r^2}\ r\ dr \end{align}Awesome! Its \(u\) substitution time.

\begin{align} &u = r^2\\ \Rightarrow &\frac{du}{dr} = 2r \\ \Rightarrow &du = 2r\ dr \\ \Rightarrow &\frac{1}{2} du = r\ dr \end{align}Supplying this into the result:

\begin{align} I^2 &= \pi \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-u}\ \ du\\ &= \pi \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{e^u}\ du\\ &= \pi \end{align}And therefore, \(I = \sqrt{\pi}\).