Table of Contents

1 Motivation: Flux

A surface integral that adds up of some amount of length \(\vec{F}\) is named "flux."

\begin{equation} \iint_S \vec{F}(x,y,z) \cdot \vec{n}\ dS \end{equation}The "flux" is the sum of some vector over a surface; Gauss' law, for instance, measures the electric flux of a surface as it is summing all of the electric charges over some surface.

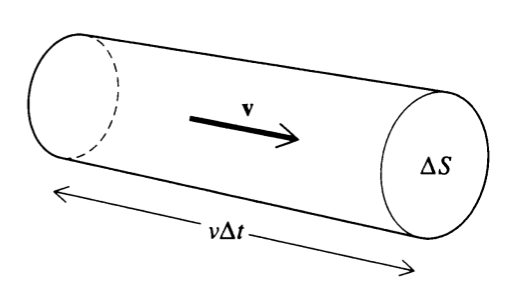

Flux can also be a way of measuring the rate of flow of something. Take, for instance, the following cylindrical tube with a cross-sectional area \(\Delta S\).

Taking a surface integral over \(\Delta S\) will tell us the rate of flow through it; that is:

\begin{equation} \iint_S \rho v \Delta S \end{equation}Represents the surface integral over \(\Delta S\) of the flow (density \(\rho\) times velocity \(v\)).

2 The Divergence

Consider some surface integral:

\begin{equation} \iint_S \vec{F} \cdot \hat{n}\ dS \end{equation}In perspective with the definition of Flux above, we can say that this is the amount of "flow rate" of something over a specific volume through a specific slice. What if, for instance, we want to know the average flow rate along a certain volume (what is the mean amount of water flowing through that point?)

Well, we would divide this surface integral by the volume for which we are calculating of surface, that is:

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{\Delta V} \iint_S \vec{F} \cdot \hat{n}\ dS \end{equation}What if, instead, this volume went to \(0\)? Instead of how much average fluid we have in a volume, we get back the density of the fluid ("how packed it is") at a point. We call this quantity the "divergence"

\begin{equation} div\ \vec{F} = \lim_{\Delta V \to 0} \frac{1}{\Delta V} \iint_S \vec{F} \cdot \hat{n}\ dS \end{equation}3 Simplified Divergence

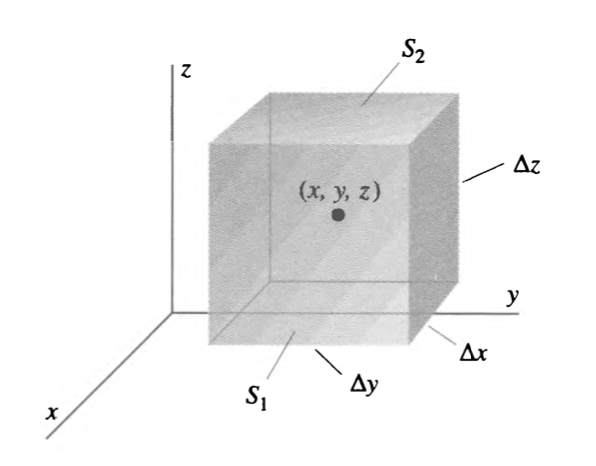

As the divergence is calculated over some infinitesimal \(\Delta V\), the surface integral which resulted in it actually does not matter in shape. Hence, we shall figure the general expression for divergence of some \(\vec{F}\) by the surface integral of an infinitesimal cube.

To figure the total surface for this infinitesimal cube, we need to consider each of the 6 faces and add them up.

Let's take the face marked \(S_1\) first (i.e. that facing us.) It is evident that the unit normal vector that this represent would be \(\hat{n} = \hat{i}\). Furthermore, \(\vec{F}\cdot\vec{i} = \vec{F_x}\). Therefore, the surface integral for that one surface would be:

\begin{equation} \iint_{S_1} \vec{F_x}(x,y,z)\ dS \end{equation}However, because we are eventually taking the limit as \(\Delta\{x,y,z\} \to 0\), we can estimate the total value on the \(S_1 = \Delta y \Delta z\) surface by taking the value of the value function at its midpoint and multiplying it by \(\Delta y \Delta z\).

If the midpoint of the whole cuboid is \((x,y,z)\), then the midpoint of the \(S_1\) would be:

\begin{equation} \left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right) \end{equation}And, therefore:

\begin{equation} \iint_{S_1} \vec{F_x}(x,y,z)\ dS \approx F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right) \Delta y \Delta z \end{equation}We can do the same thing for the opposite face:

\begin{equation} \iint_{S_2} \vec{F_x}(x,y,z)\ dS \approx -F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right) \Delta y \Delta z \end{equation}Adding these two things up, we will get that:

\begin{equation} \iint_{S_1 + S_2} \vec{F_x} \cdot \vec{n}\ dS \approx \left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right) \Delta y \Delta z \end{equation}Ok, now, we will multiply the right side by \(\frac{\Delta x}{\Delta x}\) to force a \(\Delta V\).

\begin{align} \iint_{S_1 + S_2} \vec{F_x} \cdot \vec{n}\ dS &\approx \frac{\left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right)}{\Delta x} \Delta x \Delta y \Delta z \\ &\approx \frac{\left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right)}{\Delta x} \Delta V \end{align}And, therefore:

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{\Delta V} \iint_{S_1 + S_2} \vec{F_x} \cdot \vec{n}\ dS &\approx \frac{\left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right)}{\Delta x}\\ \end{equation}We are now pretty much primed to calculate the divergence w.r.t. these two faces:

\begin{align} div\ \vec{F_x} &= \lim_{\Delta V \to 0}\frac{1}{\Delta V} \iint_{S_1 + S_2} \vec{F_x} \cdot \vec{n}\ dS \\ &= \lim_{\Delta V \to 0} \frac{\left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right)}{\Delta x} \end{align}As \(\Delta V \to 0\), we know that \(\Delta x \to 0\). As the right side contains no infinitesimal lengths except \(\Delta x\), we can substitute \(\Delta x \to 0\) for \(\Delta V \to 0\). And, therefore:

\begin{equation} \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{\left(F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2}, y, z\right)\right)}{\Delta x} \end{equation}Congratulations, you just defined a partial integral about \((x,y,z)\) w.r.t. \(x\).

Therefore,

\begin{equation} div\ \vec{F_x} = \frac{\partial F_x}{\partial x} \end{equation}We will do this again, w.r.t. every variable (3 pairs of sides). Overall, we will get:

\begin{equation} div\ \vec{F} = \frac{\partial F_x}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y} + \frac{\partial F_x}{\partial z} \end{equation}which, evidently, is much simpler than the formal definition of

\begin{equation} div\ \vec{F} = \lim_{\Delta V \to 0} \frac{1}{\Delta V} \iint_S \vec{F} \cdot \hat{n}\ dS \end{equation}