Table of Contents

1 Vector Functions

Functions like \(y=f(x)\) is a rule that associates two number \(x\) and \(y\). More generally, a function associates a (possibly multi-dimensional) set of values in perspective of others.

Vector functions, like vectors, could be resolved into the components that will output results for each of the dimensions.

Here's a basic vector function:

\begin{equation} \vec{F}(x,y) = \hat{i}x+\hat{j}y \end{equation}For vector functions, we could split it into components. Some people use the following expression for partial derivatives, though in this case we will use it for components of the vector-valued function.

For the function above, for instance, we could parameterize upon the output dimension:

- \(\vec{F}_x = x\)

- \(\vec{F}_y = y\)

Instead of being partial derivatives, we use the subscript notation for parameterization when dealing with vector value function.

2 Electrostatics

To understand the rest of the text better, the book provides a brief conversation upon electrostatics.

2.1 Charges

Two changes, positive and negative. Every piece of material contains electric charge, though most material has zero net charge by having equal parts positive and negative charges.

2.2 Coulomb's Law

Electrostatic forces between two particles are…

- Proportional to the product of their changes

- Is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them

- Acts along the line joining them

2.2.1 Formula for Coulomb's law

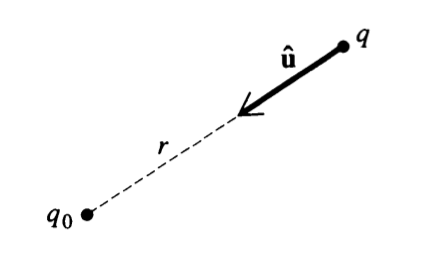

Expanding \(K = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\), we arrive at

\begin{equation} \vec{F} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{qq_0}{r^2}\hat{u} \end{equation}Looking at the numerator of this expression, we arrive at:

\begin{equation} qq_0 \hat{u} \end{equation}2.2.2 Like changes repel, unlike changes attract

One will realize that, if \(q,q_0\) have the same signs, they will have a positive \(qq_0\). Therefore, \(+\hat{u}\) will be pointed towards each other — meaning the charges will direct force towards themselves and hence repel; in a similar vein, if \(q,q_0\) have different signs, they will have a negative \(qq_0\), \(-\hat{u}\) will be pointed away from each other and hence the particles will push themselves towards each other.

Therefore: "like changes repel, unlike changes attract."

2.2.3 Principle of Superposition

If there are three changes, \(q_0\), \(q_1\), \(q_2\), and \(\vec{F}_1 \Rightarrow q_1 \to q_0\), \(\vec{F}_2 \Rightarrow q_2 \to q_0\): the total net force on \(q_0\) is \(\vec{F}_1 + \vec{F}_2\).

2.2.4 The "Electrostatic Field"

The electrostatic field is the field that a change emits given one test change, though not counting the interaction of the test change.

\begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{r}) = \frac{\vec{F}(\vec{r})}{q_0} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{r^2}\hat{u} \end{equation}So then, if we expand this same principle to \(N\) number of test changes, though all discounting their influences:

\begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{r}) = \sum^N_{i=1} \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}-\vec{r}_i|^2}\hat{u} \end{equation}2.3 Doing Some Calculus

We first define the average change density in some space \(\Delta V\) as…

\begin{equation} \bar{\rho}_{\Delta V} = \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta V} \end{equation}As in, if we treat some volume \(\Delta V\) as a continuous space, in it there exists some \(\Delta Q\) which is the total electric change in that area.

With this information, we could define the change density of any given point \((x,y,z)\) in space as function \(\mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^1\)

\begin{equation} \rho(x,y,z) = \lim_{\Delta V \to 0} \bar{\rho}_{\Delta V}\ (about\ x,y,z) \end{equation}Going the other way, we could integrate this expression, per our previous expression for the electrostatic field, it could be presented as an integral

\begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{R}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \iiint_V \frac{\rho(\vec{r})\hat{u}\vec{r'}}{|\vec{r}-\vec{r}'|^2} dV' \end{equation}(triple integral over area \(V\) and every point in it.)

3 Exercises

3.1 1.4

An object moves in the x-y plane in such a way that its position vector \(\vec{r}\) is given as a function of time \(t\) by:

\begin{equation} \vec{r} = \hat{i}a\ cos(\omega\ t) + \hat{j} b\ sin(\omega t) \end{equation}Where \(a,b,w \in \mathbb{F}\) and are constants.

3.1.1 Magnitude

How far away is the object from the origin at any time \(t\)

The object is, at any time \(t\), the following magnitude away from the origin:

\begin{equation} \sqrt{a^2\ cos^2(\omega\ t) + b^2\ sin^2(\omega\ t)} \end{equation}3.1.2 Derivatives

Find the object's velocity and acceleration as functions of time

As the function is \(R^1 \to R^2\), there are no partial derivatives to be taken. Hence:

\begin{equation} \vec{r}' = \omega(-\hat{i}a\ sin(\omega\ t) + \hat{j} b\ cos(\omega\ t)) \end{equation} \begin{equation} \vec{r}'' = -\omega^2(\hat{i} a\ cos(\omega\ t) + \hat{j} b\ sin(\omega\ t)) \end{equation}3.1.3 Tracing Path

Show that the object moves on the elliptical path

\begin{equation} \left(\frac{x}{a}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{y}{b}\right)^2 = 1 \end{equation}

We will split the original expression into components:

\begin{equation} \begin{cases} \vec{r}_x = a\ cos(\omega)t\\ \vec{r}_y = b\ sin(\omega)t\\ \end{cases} \end{equation}Therefore, we substitute the expressions for \(x\) and \(y\) components:

\begin{align} &\left(\frac{a\ cos(\omega\ t)}{a}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{b\ sin(\omega\ t)}{b}\right)^2 = 1 \\ \Rightarrow & cos^2(\omega\ t) + sin^2(\omega\ t) = 1 \\ \Rightarrow & 1 = 1 \end{align}QED

3.2 1.5

A charge \(+1\) is situated at the point \((1,0,0)\) and a change \(-1\) is sitting at the point \((-1,0,0)\). Find the electric field of these two changes at an arbitrary point \((0,y,0)\) on the \(y\) axis.

A vector-valued function representing an electric field is:

\begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{r}) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{r^2}\hat{u} \end{equation}We need to find a direction vector \(\vec{u}\) pointed towards our arbitrary-point test-charge on \((0,y,0)\).

3.2.1 Identifying the Direction Vectors

For change \(+1\), the vector pointing from our change to the arbitrary test point is:

\begin{equation} \begin{bmatrix} 0-1 \\ y-0 \\ 0-0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ y \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}Normalising this vector, therefore, we arrive the \(\vec{u}_{+1}\):

\begin{equation} \vec{u}_{+1} = \begin{bmatrix} -\frac{1}{1+y^2} \\ \frac{y}{1+y^2} \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}In a similar vein, for change \(-1\), the vector pointing from our change to the arbitrary test point is:

\begin{equation} \begin{bmatrix} 0+1 \\ y-0 \\ 0-0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ y \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}Normalising this vector, therefore, we arrive the \(\vec{u}_{-1}\):

\begin{equation} \vec{u}_{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{1+y^2} \\ \frac{y}{1+y^2} \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}3.2.2 Writing an Electric Field

Our distance, \(r^2\), is the magnitude of the distance vectors as pointed above, which is \(1+y^2\). Our direction vectors are determined above.

\begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{r})_{+1} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{1+y^2} \begin{bmatrix} -\frac{1}{1+y^2} \\ \frac{y}{1+y^2} \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \vec{E}(\vec{r})_{-1} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\frac{q}{1+y^2} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{1+y^2} \\ \frac{y}{1+y^2} \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}